Calling God a chicken – Psalm 139, Luke 13:31-35

I was going to begin the sermon by asking all of you – If God was an animal, what animal would that be? But we’ve already covered that in the children’s talk and Jesus’ answer, in our Luke passage, is still surprising! Of all the animals Jesus could identify with in his ministry of freeing people from different forms of oppression or healing people who were sick or confronting the powers that keep people oppressed, he chooses a chicken. Why would Jesus call himself a chicken!

As a young Christian feminist, I treasured this passage because, in a church where the language and images of God, the models of divine leadership, were exclusively male (and I, therefore, as female, was always other and secondary) here was one of the few – it seemed – examples of God identifying as female. And yet the image of Jesus as mother hen is still a difficult one. As writer Debie Thomas says, “If maternal power, acumen or success were the characteristics Jesus wanted to emphasise in his choice of metaphor, he could have used any number of more appropriate Old Testament images to make his point. God as enraged she-bear (Hosea 13:8). God as soaring mother eagle (Deuteronomy 32:11-12). God as labouring woman (Isaiah 42:14). God as mum of a healthy, happy toddler (Psalm 131:2). God as skilled midwife (Psalm 22:9-10).” But Jesus doesn’t choose any of these powerful, smart or successful female images. Instead, he calls himself a chicken, a mother hen calling for her chicks, whose wings are open, whose body is vulnerable, and whose young refuse to return.

Why does Jesus call himself a chicken? Perhaps, firstly, because he chooses a path of vulnerability just as the mother hen does.

I have some experience with chickens. Growing up in West Papua there were always chickens scratching in the ground around you or roosters crowing through the night. (The idea that roosters only crow at dawn is nonsense! They seemed to simply crow to compete!) Most of these chickens could fly, if in danger, up into the trees, but we clipped our chickens’ wings, so if you approached them, they squatted, and you could pick them up. Broody hens and hens with chicks, of course, were a different story. They would fluff their feathers to make themselves look larger, gather their young and hiss and peck at your hands.

But I found out how vulnerable chickens are the hard way. Confession time! When I was seven years old, I decided to try and catch one of the local chickens and I chased a hen with fairly mature chicks. She could have lifted off into the trees, but she wouldn’t leave her young. So, they were running, and I was running, and I stepped clumsily and one of the chicks was squashed beneath my foot. It was the most awful thing. As a seven-year-old whose identity centred on being an animal lover I knew I’d done something terrible.

In our Luke passage, Jesus acknowledges his vulnerability. The Pharisees – we’re not clear what their motivation was – come to tell him that Herod – Herod Antipas who killed John the Baptist – wants to kill him. “Listen,” says Jesus, “I am casting out demons and performing cures today and tomorrow, and on the third day I finish my work.” The phrase Jesus repeats, “Today, tomorrow and the next day…” is a common biblical expression to describe a short time. So, in one sense Jesus is saying, “Don’t worry. I’ll be done here soon.” But the word for ‘finished’, teleio in Greek, has the same ambiguity as in English. ‘Finished’ can also mean ‘finished off’! Jesus is also saying, “Don’t worry. I’ll be done for here soon!”

And verse 33 reinforces this meaning: “It is impossible for a prophet to be killed outside of Jerusalem.”

Jesus calls himself a chicken because as a prophet of God – as someone who wants to keep freeing people and healing people and confronting the religious and political powers that oppress people – he chooses to make himself vulnerable.

Secondly, Jesus calls himself a chicken because – ironically – he demonstrates courage.

There are different sorts of courage and self-giving love. We have seen many examples, over the last couple of weeks, of people behaving with wonderful courage and generosity, rescuing people in tinnies from floods, offering food and blankets and shelter, here in Australia and far away in eastern Europe.

Then there is this extraordinary kind of courage: to steadfastly choose a path – a path that is good and right – but which leads to one’s own disadvantage, danger, suffering and even death. In Luke 9:51 we are told that this is what Jesus does. He sets his face to go to Jerusalem. He demonstrates this extraordinary courage, the courage of a mother hen who holds out open, sheltering wings regardless of the cost.

There is a story from the National Geographic several years ago that illustrates this. After a severe bush fire (or forest fire in their case) in Yellowstone National Park, rangers began to trek up a mountain to assess the damage, and one ranger found a bird literally petrified in ashes, perched on the ground at the base of a tree. Disturbed by the eeriness of the sight, he knocked the bird with a stick. And when he struck it, three tiny chicks scurried out from under their dead mother’s wings.

The mother, aware of the impending danger and disaster, had carried her offspring to the base of the tree and gathered them under her wings. She could have flown to safety but had refused to abandon her babies. When the blaze arrived and the heat scorched her small body, she had stayed steadfast. Because she had been willing to die, those under the cover of her wings had lived.

If you saw the ABC news last night, there was another example of this, of a mother rescued from the Mariupol maternity hospital that was bombed by the Russian military who had then given birth to a baby girl, and there she was, nestled in the crook of her mother’s arm, her mother offering, to the greatest extent that she could, the protection of her body.

“Jerusalem…How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings…” Jesus calls himself a chicken because he demonstrates this vulnerable and courageous love.

Thirdly, Jesus calls himself a chicken because, his desire too – his deepest desire and longing – is for the life and flourishing of the scattered and wayward, endangered chicks.

I have another chicken confession. When I was 13 and had come back to Australia to live with my aunt and uncle to go to school, I was charged with looking after their chickens. I fed them in the morning, collected the eggs, let them out after school for a few hours and then locked them back into their pen at night. But one night I forgot. And that night the fox came. And the fox killed every single one of them. He didn’t eat any of them. He just killed them.

This is who Herod is, Jesus is saying. Herod is a fox. He wants to kill me because his desire is to take life, to play with the lives of others. Life does not matter to him, other people’s lives do not matter to him, human flourishing does not matter to him. All that matters to Herod is Herod! My desire, however, says Jesus, what I have desired to do, is to gather people, to bring people back into right relationship with God and with each other, to see community at work, to see people fed, to see people healed, to see people freed, to see life and life in all its fullness. This is my desire.

We have spoken about Jesus’ willingness to be vulnerable. We have spoken about Jesus’ courage. Perhaps that willingness to be vulnerable and that courage to keep walking the path of vulnerability find their source – find their strength and steadfastness – in this deep desire to see God transform our world, to be part of God’s transforming of our world.

I have been reflecting lately that ministry can sometimes feel like having to hold your hand in the fire. It will hurt. You will hurt. You will be burnt. But you hold it there – you keep doing your work – because your deep-down desire too is to be part of God’s lifegiving work.

Which brings me to the tragic story of Edward Wightman (1580 to the 11th April 1612) which I came across while reading about Thomas Helwys (Wightman died the year Helwys published The Mistery of Iniquity (sic).) Some call him the first Baptist martyr, but he was not a Baptist, although part of the wider anabaptist Separatist movement. He was however the last person to be burned at the stake in England for the charge of heresy.

The story of his execution is horrific (you might want to put your hands over your ears) but it is also an incredible story of vulnerability, courage and that deep desire to do God’s work.

Wightman was condemned by James I and ordered to burned at the stake. When he was brought to the stake, however, his courage left him, and he cried out, it is said, to recant and was pulled from the fire, though by then he had been, “well scorched”. Two or three weeks later, however, he was again brought before the courts and, the report is, no longer fearing the searing flames, refused and “blasphemed more audaciously than before”. The King quickly ordered his final execution, and on 11 April 1612, he was once more led to the stake. Again, feeling the heat of the fire, he would have recanted, but the sheriff ordered more faggots set to him and he was burned to ashes.

(You can take your hands off your ears now.) It is a horrific story, but it’s a very real one, and despite his very understandable desire to avoid burning at the stake, I don’t think you could call him a chicken, but you could call him a chicken, a mother hen, for his example of vulnerability, courage, and conviction.

There is a third time desire is mentioned in our Luke passage. Not Herod’s desire to kill. Not Jesus’ desire to bring life and life in all its fullness. But the people’s lack of desire to return to God, to relationship with God, to right ways of living with God and with each other. “How often have I desired to gather your children [Jerusalem]… as a mother hen gathers her brood under her wings [but] you were not willing!”

Why do we come together to worship God, to worship God with all of our lives, to be part of the body of Christ, to be a church together? I think it is because we have this same desire that Jesus had – to see human beings flourish, to see people freed, to see people healed, to see people fed, to see people living in peace and in right relationship with one other, to see people finding this life-giving God who longs to cast warm and welcoming wings over us all.

So I want to say this. This church needs to be a place where people can be inspired – where life-giving visions of what God is calling us to – can be sparked and fanned into flame. This church needs to be a place where people who are finding themselves burnt by the fire can be encouraged, can be supported, can be strengthened to remain steadfast in God’s work. This church needs to be a place, where – to refer again to that Friedrich Buechner quote that Lisa Churcher used – “people’s deep gladness and the word’s deep hunger meet.” This is our role as the church. If we are not doing this, if we are unwilling to do this, the chicks will scatter. They will not be inspired in their God-given vision of life. They will not be supported in their God given visions of life. We will miss out on being part of God’s transforming work.

Let us be people who run to Jesus as a mother hen now. Let us be people who follow Jesus as a mother hen now. Let is not be those who wait till some final day to say, “Blessed be the one who comes in the name of the Lord.”

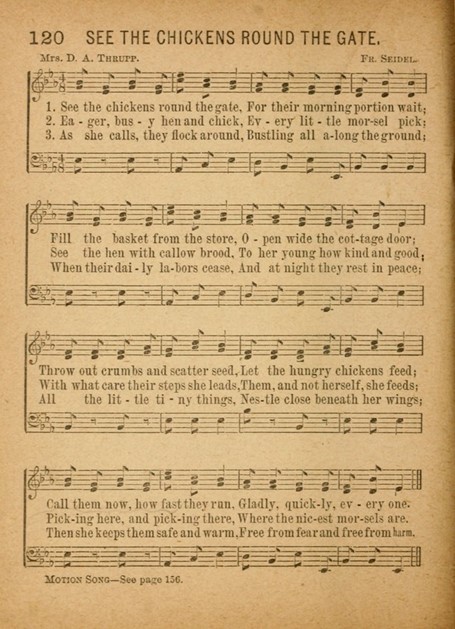

“The love of God comes close where stands an open door” – where sheltering open wings are held out to gather us and empower us to walk the way of vulnerability, the way of courage, the way of life and love. Let us sing this together.

Now, my little child, attend:

your almighty Father, Friend,

though unseen by mortal eye,

watches o’er you from on high.

As the hen her chickens leads;

shelters, cherishes and feeds,

so by God your feet are led,

over you God’s wings are spread.